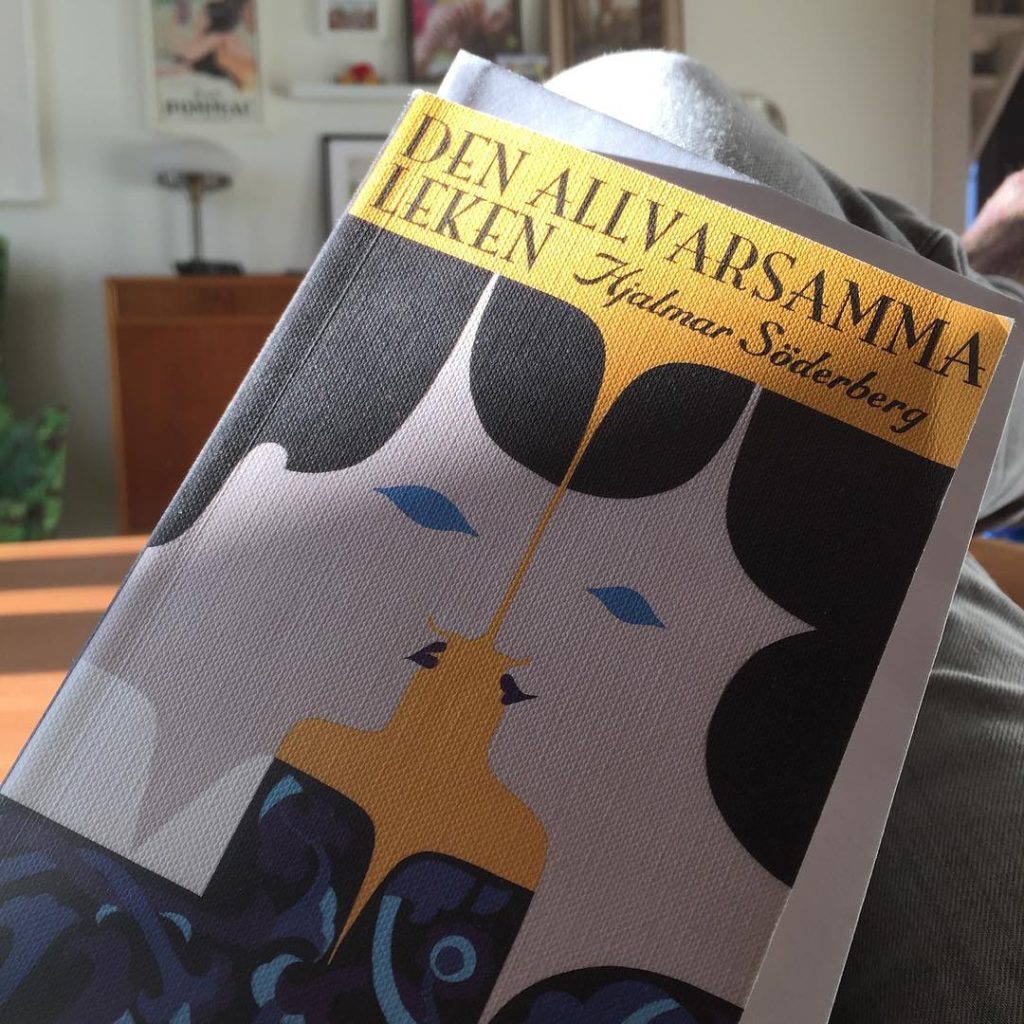

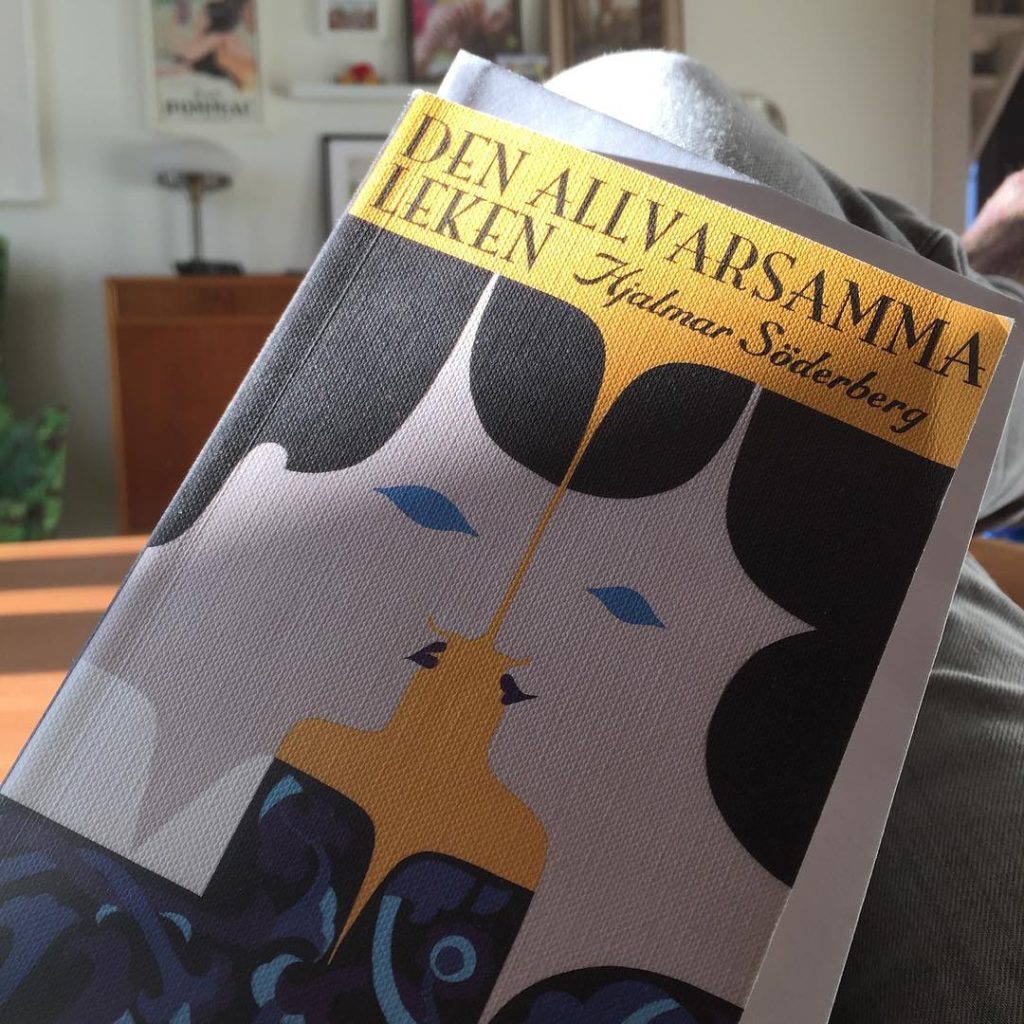

[For some reason I wrote this in English, though I read the book in Swedish.]

We follow the life of Arvid Stjärnblom, a young, intelligent young man of lower middle-class origin. Not an educated man, but intellectual nonetheless. He becomes a journalist after passing on the opportunity to study to become a teacher.

He falls in love with a young girl, Lydia Stille, the daughter of a once famed Swedish painter. But their love can never quite be. Arvid feels he cannot offer marriage, as he’s not in a financial position to provide a comfortable life for her. And though the two lust for each other, he does not want to persuade her into lewdness, because “should he succeed he’d lose respect for her, and should he fail he’d lose respect for himself.” Ultimately Lydia marries an older, well-to-do historian and author, and moves from Stockholm to live with her husband in the countryside.

Arvid often uses his and Lydia’s unrealised love as a springboard for philosophies on moral and duty. However, he does not always live by high moral principles, as he has flings and love interests, and fathers an illegitimate child. (A child that he acknowledges and “does right by” by securing adoption into a good home and by paying support.)

He becomes secretly engaged to Dagmar Randel, the daughter of a semi-successful businessman. After a while she tricks him into outing their involvement and he finds himself in an involuntary marriage. Though he’d rather remain “free”, the marriage is not without happiness and mutual respect.

With age, perhaps corrupted by his peers, who seemingly more often than not keep mistresses, Arvid becomes less occupied by moral qualms, and feels less obliged to his wife. When Lydia gets in touch with him, after a decade of no contact, they promptly engage in a love affair.

Set in Stockholm during the late 19th and early 20th century, this book appeals to those fascinated by life during this period. It gives us an insight into the, many times unhappy lives of the middle class. Where marriage is more of a financial agreement than the result of passion, and family life becomes a prison.

There are parallels between Hjalmar Söderberg’s own life and that of Arvid Stjärnblom. It’s no secret that Lydia Stille is based on Maria von Platen, who for a time was Söderberg’s mistress. That said, Söderberg tries to deny the links between the story and his own past by having the character Rissler, an author and playwright, explain how everything in his salacious writing is made up, and not self experienced. He goes on to blame August Strindberg for leading the public to think everything an author puts on paper is autobiographical.

The book still feels relevant a hundred years after it was written. The prose is beautifully crafted. Flowing easy, though dated in some expressions and the formality with which the characters converse.

On its release in 1912, it must have been seen as quite risqué, especially Lydia Stille. After divorcing her husband she lives a “free life” mainly reserved for the male sex back then. As the story unfolds, she keeps several lovers, and vows to never marry again.

In the end Arvid’s life falls apart. Dagmar finds out about his infidelity, but refuses to divorce, and he cannot accept that Lydia is involved with other men, ending their relationship.

Categorising The Serious Game as a love story would not be incorrect, but there are several morals to this story. One that keeps popping up is formulated by a colleague of Arvid’s, regarding love and family: “You don’t get to choose.” Your fate is sealed. You don’t get to choose your parents, your wife, your children. You get them, have them, and perhaps lose them. But you don’t get to choose.

At the same time, I feel that Söderberg argues against this fatalist notion, between the lines.

Arvid’s life is largely formed by his own inability to choose and decide. He does not choose to study to become a teacher, he sticks with journalism, a job he gets largely by coincidence.

He chooses not to pursue the love of Lydia, under the pretence that he cannot give her the life she deserves, though he simply does not want to settle just yet. He does not want to marry Dagmar, because he does not want to get stuck with her, as he seems to think he can do better. Even when offered a second chance with Lydia, he finds reasons not to marry her. And though he eventually feels great remorse in doing Dagmar wrong, he never acts on these feelings. Never tries to do right until his hand is forced, by which time it is too late.

Perhaps Söderberg is telling us that one can’t let haphazardness run life, and then thinks of it as fate. That a man is not judged and rewarded by his thoughts and philosophies alone, but by his actions and decisions.

It’s tempting to view Arvid as the victim of circumstance, while in fact he’s a victim of his own cowardice and fear of commitment.